Hi, I'm Marisa. I'm a graduate student in Interpreting Studies at Western Oregon University, a Certified Healthcare Interpreter (CHI-Spanish), a CCHI Commissioner, and I've been a practicing healthcare interpreter since 2006. Through my work with Tica Interpreter Training and Translations (Tica TnT), I train medical interpreters across the country. This blog is where I process what I'm learning in grad school, reflect on nearly two decades of experience, and share insights that I hope will support the field. I'm using this space to educate myself—and bring what I learn back to the interpreters and LEP patients we serve every day.

Medical Interpreting as a Practice Profession:

Reflections for Interpreters and Educators

May 5, 2025

Written by Marisa Rueda Will, CHI-Spanish

As an interpreter trainer and content creator, my mind is constantly spinning with new ways to process what I'm learning and pass it on to others. This past year as a graduate student at Western Oregon University, I've done a lot of academic reading—reading that is reshaping how I teach and how I view my role in interpreter education.

One of the most transformative concepts I've encountered is the idea that medical interpreting is a practice profession. According to Dean and Pollard (2005), interpreters

"cannot deliver effective professional service armed only with [their] technical knowledge of source and target languages, culture, and a code of ethics… [they] must supplement [this] with input, exchange, and judgment regarding the consumers [they] are serving in a specific environment and in a specific communicative situation" (p. 259).

In plain terms: we are not just language machines. We are skilled professionals making real-time decisions, analyzing interpersonal dynamics, and adapting to context-specific needs—just like other members of the healthcare team.

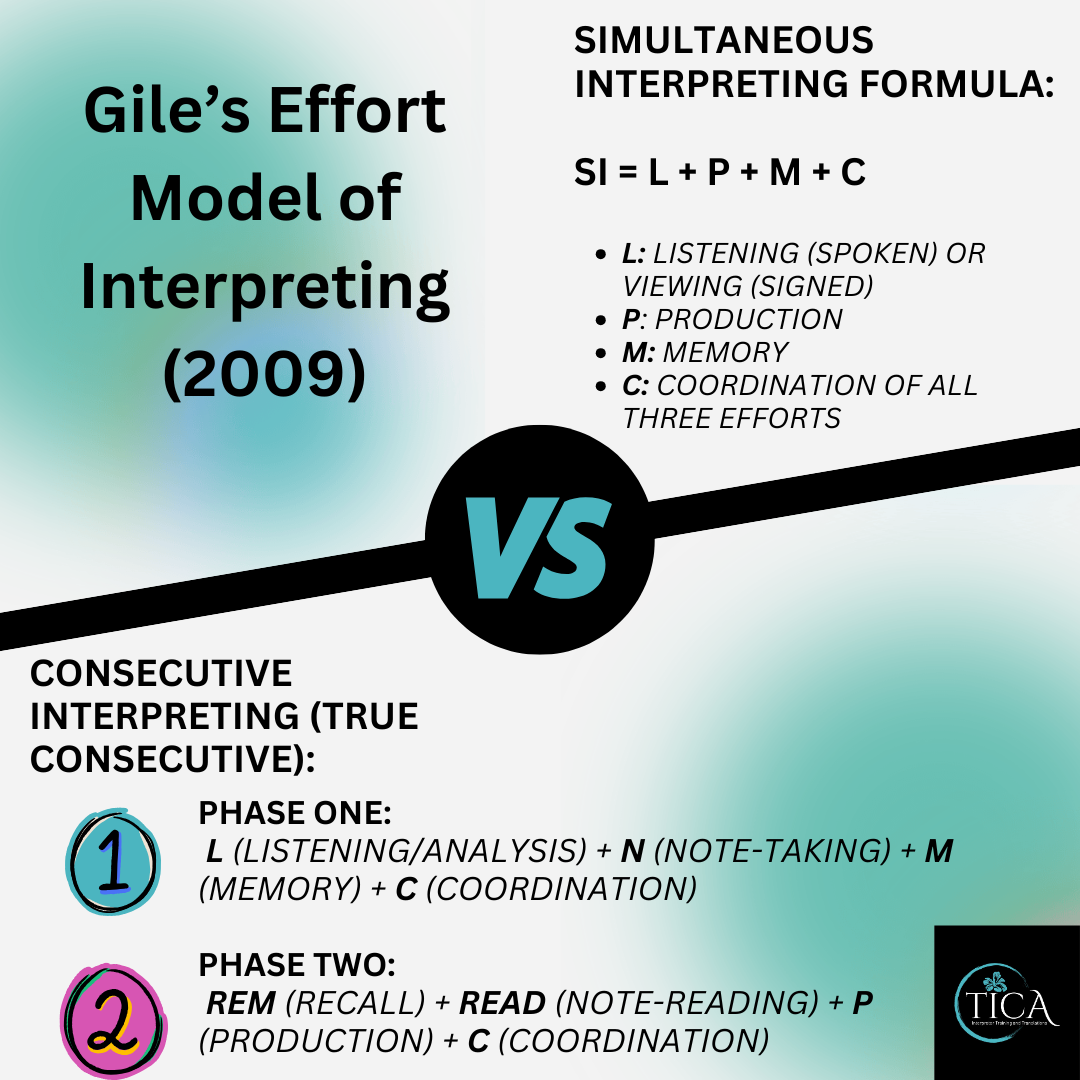

Theory as a Tool: The Effort Model of Interpreting

One framework that helped me better understand the cognitive load of interpreting is Daniel Gile's Effort Model (2009). This model illustrates how various mental processes must be managed simultaneously in real-time language transfer.

Simultaneous Interpreting Formula:

SI = L (Listening) + P (Production) + M (Memory) + C (Coordination)

True Consecutive Interpreting (Two Phases):

Phase 1: Listening + Note-taking + Memory + Coordination

Phase 2: Recall + Note-reading + Production + Coordination

Rethinking Consecutive: Are We Actually Teaching It Correctly?

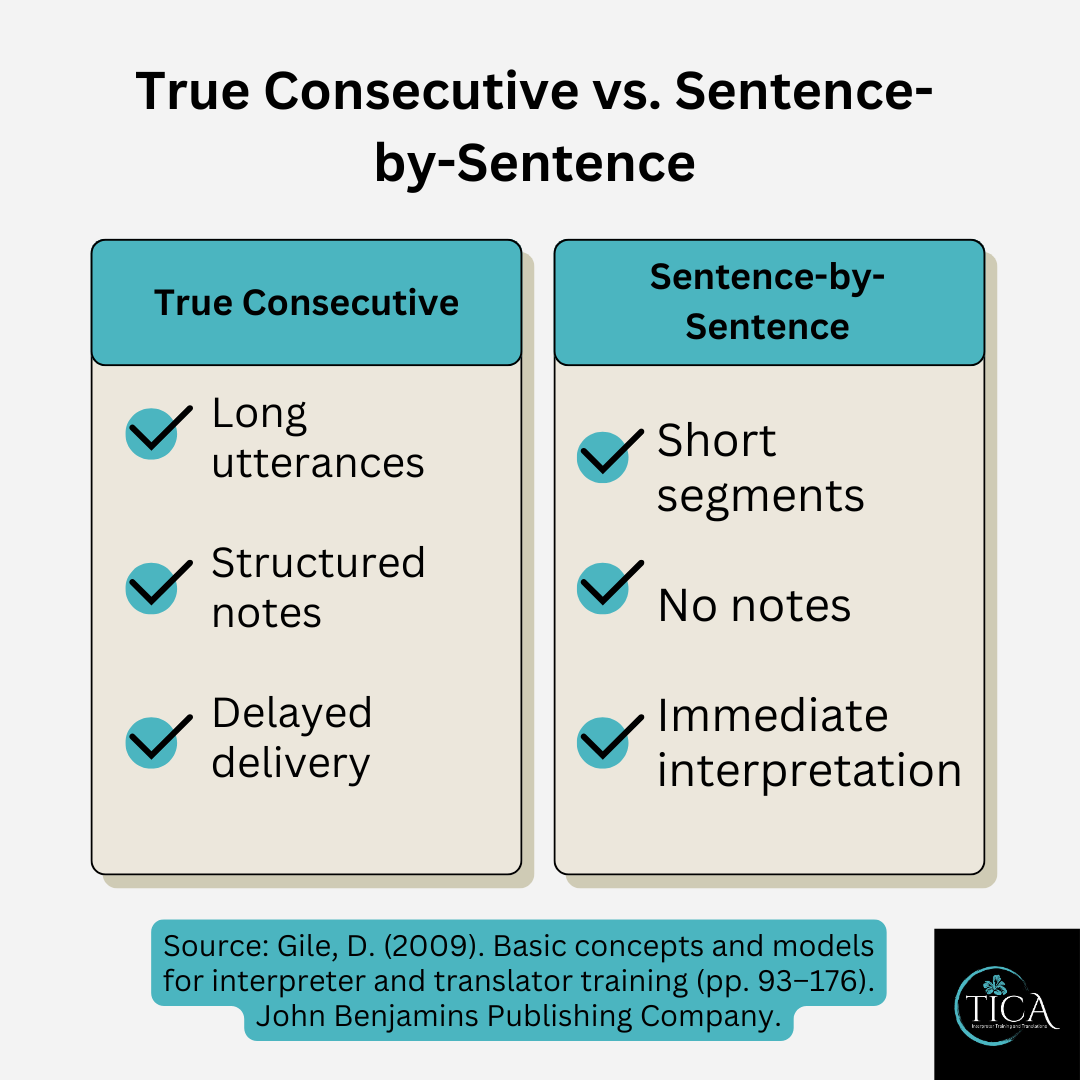

One of the most eye-opening moments for me this year came when I read Gile's definition of true consecutive. What many of us call "consecutive" isn't consecutive at all.

"True consecutive… is classified as when the speakers' uninterrupted utterances are at least a few sentences long, as opposed to sentence-by-sentence in which there is no systematic note-taking" (Gile, 2009, p. 175).

Let that sink in.

If you're pausing the provider after every sentence and calling that consecutive interpreting—but you're not using structured notes—you're not teaching or practicing true consecutive.

This realization should serve as a wake-up call for interpreter educators and practitioners alike. How often do we:

Teach "slow it down" without teaching memory retention strategies?

Default to sentence-by-sentence interpreting out of habit or convenience?

Avoid systematic note-taking because we assume it's too advanced?

True consecutive demands different strategies, deeper processing, and intentional training. It's not about control—it's about complexity.

Process-Based Learning: Teaching the "How," Not Just the "What"

Another framework I found impactful comes from González Davies (2005), who promotes a process-based approach to interpreter education. Rather than just measuring the final product, this model values how students get there.

"An awareness of the translation strategies and solutions used by professional translators is reinforced by students' reflection on those they use themselves… This approach increases their self-confidence… and contributes to greater coherence, quality, and speed" (p. 74).

By encouraging students to reflect on their strategies, we help them build confidence, accuracy, and speed.

When Language Pairing Isn't Possible: English-to-English (EtoE) as a Training Tool

A common challenge in interpreter education is working with students who don't have a practice partner in their language pair. My proposed solution: English-to-English training using skill-specific exercises.

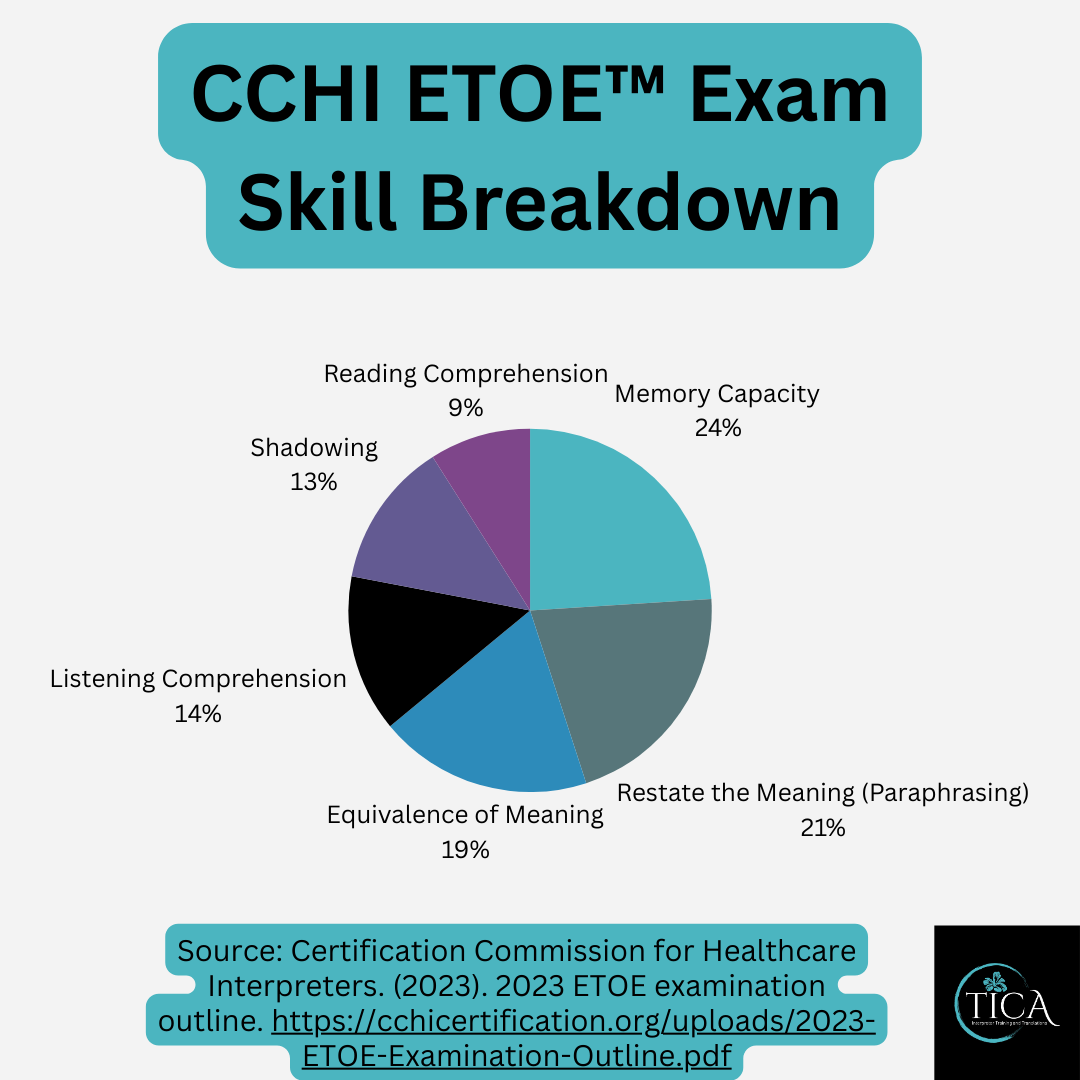

The CCHI ETOE exam already provides a solid framework. It assesses core competencies that every interpreter can develop—even without a bilingual partner.

To support this, I created a free paraphrasing activity that's entirely in English:

🎥 Watch the exercise on YouTube

This model gives students the chance to practice processing, reformulating, and retaining meaning—all without needing a partner.

Final Thoughts

Medical interpreting is complex, cognitive, and contextual. We are not passive conduits—we are dynamic, thinking professionals. The more we embrace process-based learning and cognitive models like Gile's, the more prepared our students (and colleagues) will be to thrive in the field.

This is interpreting as a practice profession. And it deserves training, attention, and respect that reflects that reality.

References

Certification Commission for Healthcare Interpreters. (2023). 2023 ETOE examination outline. https://cchicertification.org/uploads/2023-ETOE-Examination-Outline.pdf

Dean, R. K., & Pollard, R. Q. (2005). Consumers and service effectiveness in interpreting work: A practice profession perspective. In M. Marschark, R. Peterson, & E. A. Winston (Eds.), Sign language interpreting and interpreter education: Directions for research and practice (pp. 259–282). Oxford University Press.

Gile, D. (2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training (pp. 93–176). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

González Davies, M. (2005). Minding the process, improving the product: Alternatives to traditional translator training. In M. Tennent (Ed.), Training for the new millennium: Pedagogies for translation and interpreting (pp. 67–82). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Fidelity, Human Connection, and the Interpreter's Evolving Role

June 1, 2025

by Marisa Rueda Will, CHI-Spanish

Fidelity to the message is the foundation of modern interpreting practice. Maintaining the autonomy of the speaker through faithful rendering cannot be compromised; it's the cornerstone of our profession. Yet, crafting meaning is not a mechanical process—it's an art. As Gile (2009) demonstrates through the exercise of showing an image to a group of interpreters and having them render its meaning, no two renditions are exactly the same. Context shapes communication, and interpreters, as human communicators, bring this nuance to life.

Now, let's take this idea a step further. Emotional intelligence research, the pandemic, and the atrophy of interpersonal relationships highlight the critical need for highly skilled communicators in medical encounters. Unlike other settings, such as court interpreting—where the wellbeing of the client isn't always considered—medical interpreters are bound by the ethical principle of beneficence. This principle, foundational to the National Council on Interpreting in Health Care's standards of practice and code of ethics (NCIHC, 2004), requires interpreters to do more than transmit words. It calls on us to detect misunderstandings, bridge disconnections, and guide patients toward the resources they need—all while preserving the patient's autonomy and dignity.

Yet, there remains a significant gap in understanding this role, especially among healthcare providers. Interpreters are too often seen as mere input-output devices—a perception that is not only demeaning but dangerous for our limited English proficient (LEP) populations. As Chipman, Meagher, and Barwise (2024) argue, limited English proficiency is itself a social determinant of health. Officially recognizing LEP as such would be a crucial step toward achieving equitable care for these patients.

Healthcare providers and interpreters working together can dismantle the barriers LEP patients face—from the moment they step into a clinic and struggle to read signage, to navigating complex conversations about consent for surgery. This collaboration doesn't happen by accident. It requires interpreters to advocate for themselves, pursue credentialing, and push for systemic support. Interpreter Services Managers play a pivotal role, crafting multipronged approaches to support interpreter growth and integration into the healthcare team. My Fostering Self-Regulated Learning for Medical Interpreters: Manager's Guide was inspired by Fink's (2013) updated version of Bloom's taxonomy, which expands learning beyond foundational knowledge and application to include critical areas such as human connection, caring, and learning how to learn. These dimensions are vital for interpreters managing the complexities of medical encounters.

But how do we communicate this message effectively? By embracing our role as skilled human communicators. Drawing from Carnegie's (1998) timeless guidance on interpersonal relationships, I believe medical interpreters need a crash course in public relations. We must learn to engage managers, healthcare providers, and potential advocates with language that resonates—stories that touch hearts and strategic words that sway minds. Picture the patient who misunderstood a pre-surgery call, fasting for three days before a consult. Or frame our contributions in terms that hospital administrators understand: social determinants of health, equitable care, cost avoidance, reduced readmission rates, and improved staff wellbeing.

Moreover, recent research by Kalenda and Vávrová (2016) underscores that self-regulated learning is shaped by a complex interplay of motivation, emotions, cognitive strategies, and social factors. Their findings point to the necessity of creating environments—like those fostered by supportive managers and organizations—that not only provide learning resources but also nurture motivation and emotional resilience. This holistic understanding of self-regulated learning is crucial for interpreters, who must adapt, learn continuously, and manage emotional challenges while serving LEP patients.

This is a team effort, and it starts with us. Whether through joining local interpreter organizations, participating in online communities, or forming peer support groups, interpreters can foster continuous learning and advocacy. Together, we can reshape perceptions, empower ourselves and our colleagues, and advance language access as a pillar of equitable healthcare.

To support these efforts, I've created a practical guide for Interpreter Services Managers, inspired by Fink's learning framework and recent research on self-regulated learning. This resource offers actionable strategies to foster growth, resilience, and professional excellence in your interpreter teams.

References

Carnegie, D. (1998). How to win friends and influence people. Gallery Books. (Original work published 1936)

Carnegie, D. (2022). How to win friends and influence people (R. Petkoff & D. D. Carnegie, Narr.) [Audiobook]. Simon & Schuster Audio.

Chipman, S. A., Meagher, K., & Barwise, A. K. (2024). A public health ethics framework for populations with limited English proficiency. American Journal of Bioethics, 24(11), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2023.2224263

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Gile, D. (2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training: Revised edition. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Kalenda, J., & Vávrová, S. (2016). Self-regulated learning in students of helping professions. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 217, 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.02.086

National Council on Interpreting in Health Care. (2004). A national code of ethics for interpreters in health care. https://www.ncihc.org/assets/documents/publications/NCIHC%20National%20Code%20of%20Ethics.pdf

Interpreting Reshapes Our Brain: What Cross-Disciplinary Research Tells Us

I've always been fascinated by the neuroscience of interpreting. There's something incredible about understanding what's happening in our brains when we do this work. As I'm nearing the end of my first year of grad school, I came across García's (2019) research showing that "significant neural and behavioral effects are detected before the first eighteen months of [interpreter] training" (p. 188). Reading that paper got me thinking about how I can use this knowledge—along with everything else I've been learning—to enhance my teaching and approach in general.

We Are Amazing! Our Brains Actually Change

Within 18 months of training, interpreter students show measurable changes in auditory perception, conceptual processing, vocabulary search, interlinguistic operations, and handling unfamiliar materials (García, 2019, p. 194). Think about that—we're not just getting better at languages. We're literally rewiring our cognitive processing systems.

And here's what really fascinated me: Hönig's research shows that self-confidence "appears as a factor coordinating and governing [mental processes] and is therefore considered to be fundamental to successful and effective translating" (as cited in Haro-Soler, 2018, pp. 78, 88). Self-confidence isn't just a nice feeling—it's your brain's executive coordinator managing all these complex processes.

Meeting Students Where They Are

This research has completely changed how I think about working with struggling students. When someone is having a hard time, I now have two different frameworks to help them, depending on what they need:

The Neurophysiological Approach: Sometimes students need to hear that their brain is literally changing with practice. When they're frustrated that progress feels slow, I can tell them it takes time—and I can back that up with actual brain science. García's research shows that significant changes happen within 18 months, which means every practice session is building neural pathways. That's powerful reassurance for students who think they're not cut out for this work.

The Psychological Approach: Other times, students need to work on confidence and self-efficacy. Haro-Soler (2018) distinguishes between general self-confidence (believing you can handle diverse situations) and task-specific self-efficacy (believing you can perform specific tasks with the exact skills needed). Some students have the skills but doubt themselves. Others need to build specific competencies. Now I can identify which is which and address it directly.

Different Teaching Approaches for Different Learners

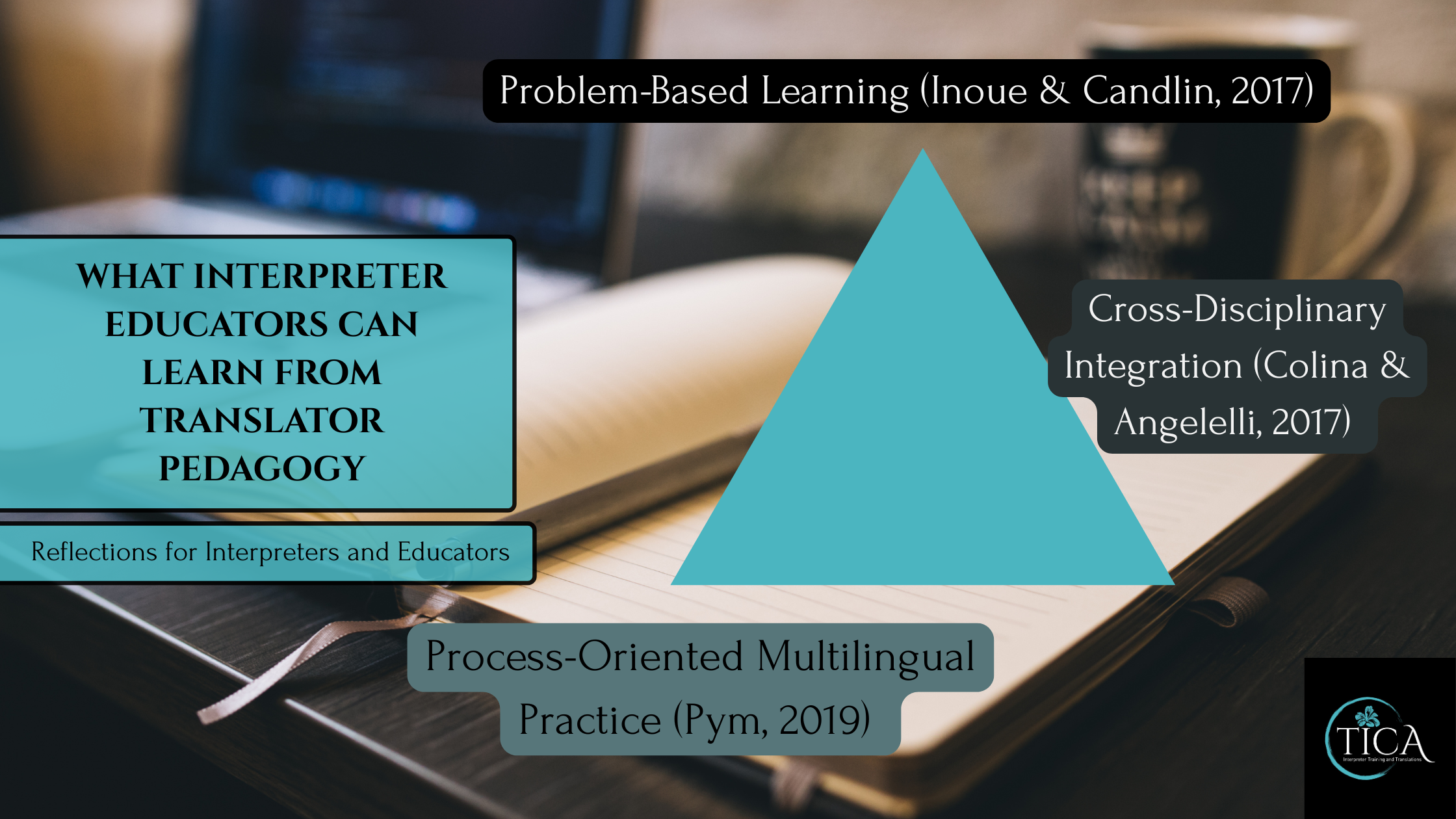

The cross-disciplinary research I've been reading has also given me a toolkit of teaching approaches:

Problem-Based Learning (Inoue & Candlin, 2017) works great for students who learn by doing. When they tackle realistic scenarios through Task-Based Learning activities, they're building the same cognitive flexibility that García identifies in brain research—but they're doing it through hands-on problem-solving.

Process-Oriented Learning (Pym, 2019) is perfect for students who need to discover things for themselves. As Pym puts it, "students are made to look for their own solutions, instinctively enacting interactive and collaborative pedagogies that are news to no one" (p. 322). This approach builds both confidence and task-specific skills through peer collaboration.

Cross-Disciplinary Integration (Colina & Angelelli, 2017) lets me pull in tools from Second Language Acquisition, technology, and constructivism. When I layer these approaches together, I'm creating learning environments that work with how different brains actually learn.

What This Means Going Forward

As I head into the final part of grad school, I'm excited about having this framework. Whether a student needs a neurophysiological approach or a psychological approach depends on where they are on their journey. Some need to understand the science behind what they're experiencing. Others need confidence-building strategies. Many need both at different times.

The research from my case study work on the Rozan method fits perfectly here. When students collaborate to figure out the seven-step consecutive note-taking system, they're engaging in exactly the kind of learning that builds both neural pathways and self-efficacy. They're discovering solutions, building confidence, and literally reshaping their brains.

We are amazing. Our brains change with practice. And now I have multiple ways to help students understand and experience that transformation.

References

Colina, S., & Angelelli, C. V. (Eds.). (2017). Translation and interpreting pedagogy in dialogue with other disciplines. John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/bct.90.01ang

García, A. M. (2019). The interpreter's brain. In The neurocognition of translation and interpreting (pp. 177–186). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.147

Haro-Soler, M. del M. (2018). Self-confidence and its role in translator training: The students' perspective. In I. Lacruz & R. Jääskeläinen (Eds.), Innovation and expansion in translation process research (pp. 131–154). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/ata.18.07har

Inoue, I., & Candlin, C. N. (2017). Applying task-based learning to translator education: Assisting the development of novice translators' problem-solving expertise. In S. Colina & C. V. Angelelli (Eds.), Translation and interpreting pedagogy in dialogue with other disciplines (pp. 55–76). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/bct.90.04ino

Pym, A. (2019). Teaching translation in a multilingual practice class. In D. B. Sawyer, F. J. Albir, & M. Gambier (Eds.), The evolving curriculum in interpreter and translator education: Stakeholder perspectives and voices (pp. 319–336). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/ata.xix.15pym

Sign Up To Receive Paraphrasing Worksheet PDF